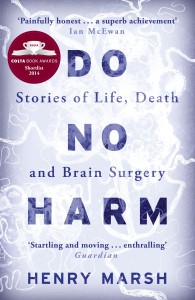

Do No Harm is a remarkably simple book. So much so, The Guardian (the book was short listed for The Guardian ‘First Book Award’) asks, ‘Why has no one ever written a book like this before?’ Each chapter’s starting point is a real life case. The clinical and extra-curricular vignettes recited allow the reader the privilege of being a fly-on-the-wall during moments of incredible personal and professional strain, sometimes during frank disaster, and occasionally during enormous relief and hilarity. In total, the book makes up a lean, unadorned, honest memoir of just some of the emotional thrills and surgical spills from a life spent in a busy tertiary neurosurgical unit. There is no twisting, confluent, fictional, engineered storyline because the quotidian of Marsh’s operating theatres, clinic rooms and foreign trips provides a surplus of heroes and heartache to sate the appetite of even the most demanding reader, publisher or dramaturge.