The early part of the 20th Century was a time of great spiritual, intellectual and artistic upheaval in Western Europe. In Vienna, Arnold Schoenberg and his pupils Anton Webern and Alban Berg, whose music we will hear in the second half of tonight's Prom, were rewriting the rules of classical music. Sigmund Freud was practising psychoanalysis in Vienna, and Jung was developing his theories of analytical psychology; the two worked closely together for several years.

Europe was heading for the First World War and on the eve of the war Jung had an almost catastrophic spiritual crisis which led him to enter in to a long and complex period of self-analysis.

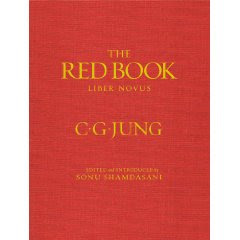

Jung recorded his psychological experiments on himself in a beautiful manuscript which he called Liber Novus (the New Book). Bound in red leather, it became known as the Red Book.

The Red Book as covered by The Cockroach Catcher in two posts:

Tuesday, September 22, 2009

Jung told one of his patients:

“I should advise you to put it all down as beautifully as you can — in some beautifully bound book,” Jung instructed. “It will seem as if you were making the visions banal — but then you need to do that — then you are freed from the power of them. . . . Then when these things are in some precious book you can go to the book & turn over the pages & for you it will be your church — your cathedral — the silent places of your spirit where you will find renewal. If anyone tells you that it is morbid or neurotic and you listen to them — then you will lose your soul — for in that book is your soul.” Read more >>>>>>>>

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Sunday, September 20, 2009

"This is a story about a

nearly 100-year-old book, bound in red leather, which has spent the last

quarter century secreted away in a bank vault in Switzerland. The book is big and

heavy and its spine is etched with gold letters that say “Liber Novus,” which

is Latin for “New Book.” Its pages are made from thick cream-colored parchment

and filled with paintings of otherworldly creatures and handwritten dialogues

with gods and devils. If you didn’t know the book’s vintage, you might confuse

it for a lost medieval tome.

And yet between the book’s

heavy covers, a very modern story unfolds. It goes as follows: Man skids into

midlife and loses his soul. Man goes looking for soul. After a lot of instructive

hardship and adventure — taking place entirely in his head — he finds it again.

Some people feel that

nobody should read the book, and some feel that everybody should read it. The

truth is, nobody really knows. Most of what has been said about the book — what

it is, what it means — is the product of guesswork, because from the time it

was begun in 1914 in a smallish town in Switzerland, it seems that only

about two dozen people have managed to read or even have much of a look at it.

Of those who did see it,

at least one person, an educated Englishwoman who was allowed to read some of

the book in the 1920s, thought it held infinite wisdom — “There are people in

my country who would read it from cover to cover without stopping to breathe

scarcely,” she wrote — while another, a well-known literary type who glimpsed

it shortly after, deemed it both fascinating and worrisome, concluding that it

was the work of a psychotic.So for the better part of the past century, despite

the fact that it is thought to be the pivotal work of one of the era’s great

thinkers, the book has existed mostly just as a rumor, cosseted behind the

skeins of its own legend — revered and puzzled over only from a great distance.

W.W. Norton & Company

“The purpose of analysis is not treatment,”

“That’s the purpose of psychotherapy. The purpose of analysis, is to give life back to someone who’s lost it.”

STEPHEN MARTIN, Jungian.

Related:

No comments:

Post a Comment